A Theoretical Foundation for Recovery Made Simple

Tim Z Brooks

Through many years of observing how addiction treatment models are applied in the real world, I have watched the field of recovery resemble an ideological battleground more than a coordinated system of care. Clinicians, programs, and communities are often asked to choose sides: spiritual or scientific, abstinence or moderation, disease or choice, structure or freedom. These divisions do not merely shape professional discourse; they shape the lived experience of people seeking help, many of whom are left feeling they must contort themselves to fit a model rather than find a model that fits their lives.

If the field is to mature, we must be willing to question the premise underlying these debates. Addiction and recovery are not unitary phenomena. They are complex, multi-dimensional processes that unfold simultaneously across biological systems, psychological structures, relational fields, cultural meaning systems, and social institutions. Any framework that privileges only one of these dimensions, however well-intentioned, will eventually fail to account for the whole person.

The foundational orientation of Recovery Made Simple is rooted in what I refer to as Integrative Recovery or an Integral Perspective on recovery. Informed by the theoretical work of Ken Wilber and the applied Integral contributions of John Dupuy, Dr. Guy Du Plessis, and Dr. Bob Weathers, this perspective functions less as a new treatment modality and more as an architectural framework: a way of designing recovery approaches that can carry the full load of human complexity without collapsing into reductionism.

Loosely defined, an Integral Perspective synthesizes insights from multiple disciplines (psychology, biology, neuroscience, sociology, and spirituality) and from multiple recovery traditions (harm-reduction, rules-based, rational-behavioral, mythopoetic, and holistic approaches) into a context-dependent framework that attends to an individual’s developmental capacities, life circumstances, and social-cultural location. While this may sound abstract, its value lies precisely in its practical application: it provides a structural map for understanding why different people require different recovery architectures at different points in their lives.

Beyond Mono-Dimensional Models

Most dominant recovery approaches emerged by foregrounding one dimension of human experience. Twelve-step traditions emphasize spiritual awakening, moral inventory, and communal belonging, offering profound resources for meaning-making and social support. Cognitive-behavioral approaches prioritize skill acquisition, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral regulation, often producing measurable and reliable outcomes. Biomedical models focus on neurochemistry, genetics, and pharmacological stabilization, offering critical tools for managing withdrawal and relapse risk.

Each of these perspectives captures something essential. The problem arises when any single approach is treated as structurally sufficient, as if it alone can bear the full weight of addiction and recovery. When this happens, dimensions that fall outside the model’s explanatory frame are dismissed or pathologized: spirituality becomes “unscientific,” biology becomes “reductionistic,” structure becomes “oppressive,” autonomy becomes “denial.”

The Integral Perspective does not attempt to resolve these tensions by declaring a winner. Instead, it reframes the problem by asking a more functional question: What dimension of the person’s experience is most salient right now, and what form of support is structurally appropriate at this stage?

Recovery and Lines of Addiction

From an Integral perspective, addiction does not express itself along a single axis. Instead, it plays out across a wide field of what Integral theory calls lines, modes, or intelligences—distinct channels through which human energy, desire, and adaptation move. Substance use is only one such line. Others include sex and love, money and spending, risk-taking behaviors such as gambling, and the regulation of attention through gaming, screens, or compulsive information consumption. Each of these lines represents a legitimate human capacity that can become distorted or dysregulated under certain conditions.

Crucially, each addictive line operates according to its own dynamics of cause and effect. Substance addictions involve biochemical reinforcement and tolerance; sexual and relational addictions often center on attachment wounds and intimacy regulation; economic and spending addictions may be driven by anxiety, identity, or social comparison; risk-taking behaviors frequently involve sensation-seeking and reward anticipation; attention-based addictions exploit cognitive novelty and dopamine-driven feedback loops. Treating these diverse expressions as interchangeable misses their specificity. An Integral approach insists on nuance, recognizing that different lines require different diagnostic lenses and intervention strategies.

At the same time, Integral theory cautions against treating any one line in isolation. A common pattern in recovery is cross-addiction, where the suppression or removal of one addictive expression leads to the emergence of another. When the underlying drivers of compulsive behavior are not addressed across the broader field of lines, addictive energy simply migrates. A person may stop drinking only to develop compulsive spending, sexual acting out, or obsessive gaming. From an Integral standpoint, this is not failure but a signal that recovery work has been applied too narrowly.

Effective recovery, therefore, requires attending to addiction wherever it arises within the field of lines and modes. This does not mean treating all behaviors as equally problematic, nor does it demand simultaneous intervention across every domain. Rather, it involves cultivating awareness of how addictive patterns express themselves differently while drawing from common underlying dynamics such as regulation of emotion, identity, meaning, and connection. An Integral Perspective understands recovery as a process of increasing freedom across the whole field of life, so that addictive patterns lose their grip not in one domain only, but wherever they might otherwise reappear.

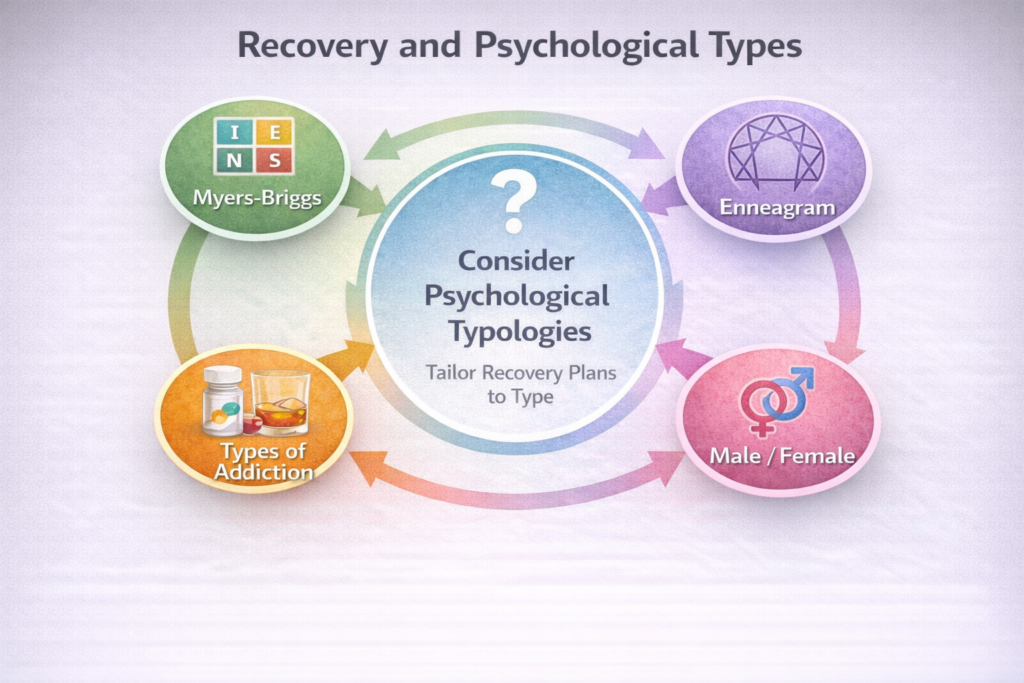

Recovery and Psychological Types

In addition to states, stages, and structures, an Integral approach to addiction recovery must also account for psychological types. Types refer to relatively stable patterns in how people experience themselves, relate to others, and make sense of the world. While stages describe how development unfolds over time, types describe how individuals are differently configured at any given stage. Ignoring type differences can lead recovery professionals to mistake mismatch for resistance, or to apply otherwise sound interventions in ways that fail to resonate with the person receiving them.

Even the simplest typologies reveal the importance of this dimension. Traditional recovery programs have long recognized the practical wisdom of pairing male sponsors with men and female sponsors with women. This practice reflects an implicit understanding that people of similar types may share embodied experiences, relational dynamics, and social pressures that foster trust and identification. While gender is only one axis of type, it illustrates a broader point: recovery unfolds within lived identities, and similarity of type can lower barriers to honesty, safety, and mutual understanding.

More nuanced personality typologies, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or the Enneagram, may also offer valuable insights, even though their application to recovery treatment remains underdeveloped. These frameworks can help clinicians and recovery guides better understand how different individuals process emotion, handle authority, respond to structure, or cope with stress. For example, an approach that emphasizes emotional disclosure and group sharing may be deeply supportive for one personality type and overwhelming or counterproductive for another.

From an Integral perspective, attending to psychological type is not about labeling or constraining people, but about increasing fit. Recovery plans are most effective when they align with how a person naturally engages the world, relates to others, and regulates inner experience. By thoughtfully incorporating type considerations alongside states, stages, and context, recovery professionals can design interventions that feel less imposed and more intrinsically workable. In this way, type awareness strengthens the central aim of Integral recovery: meeting people where they are, not where a model assumes they should be.

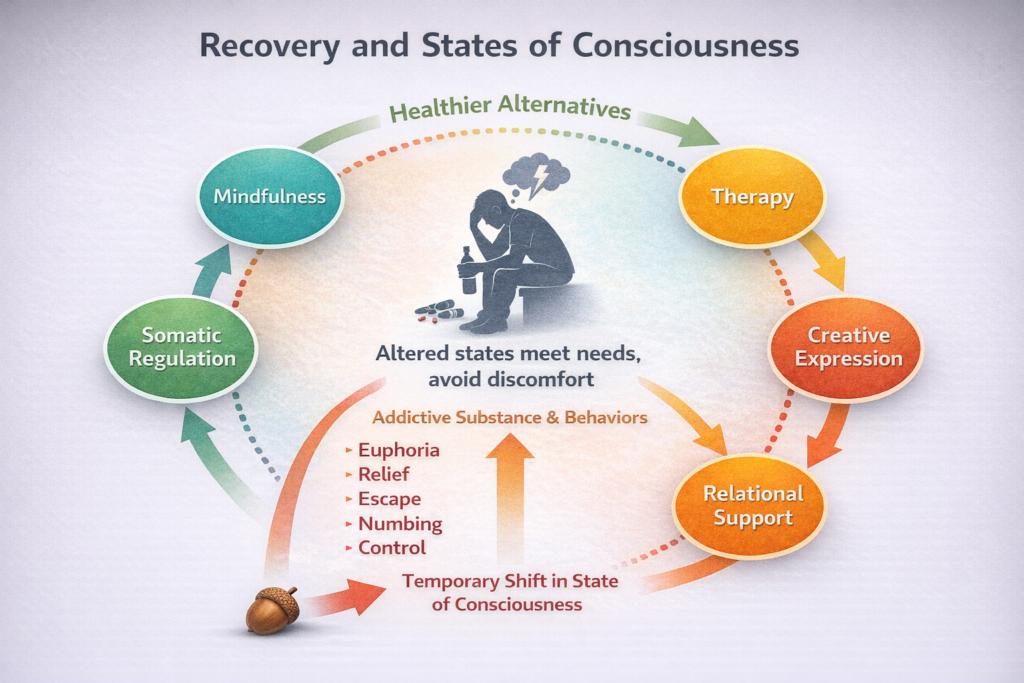

Recovery and States of Consciousness

Nearly all forms of addiction, from compulsive spending to heroin use, share a core function: they alter states of consciousness. Substances and behaviors are used not simply for their external effects, but because they reliably change how a person feels, perceives, and inhabits reality. Addiction, in this view, is less about the object of use than about the state it produces, whether that state offers relief, emotional numbing, stimulation, control, or temporary transcendence.

From an Integral perspective, people do not merely engage in addictive behaviors; they enter altered states through them. Over time, these states become dependable tools for regulating emotional and physiological experience. What appears externally as self-destructive behavior often functions internally as an improvised form of state regulation.

An Integral approach therefore asks how a person experiences reality through states, what needs those states are meeting, and what feels intolerable without them. Rather than treating altered states as pathological, Integral recovery views them as meaningful signals pointing to unmet needs and underdeveloped capacities.

If addiction is partly an attempt to manage consciousness, recovery must involve healthier ways of meeting those same needs. Practices such as mindfulness, somatic regulation, therapy, creative expression, relational support, and spiritual practice can offer alternative pathways. The aim is not to eliminate the human drive to alter consciousness, but to expand it into life-affirming forms.

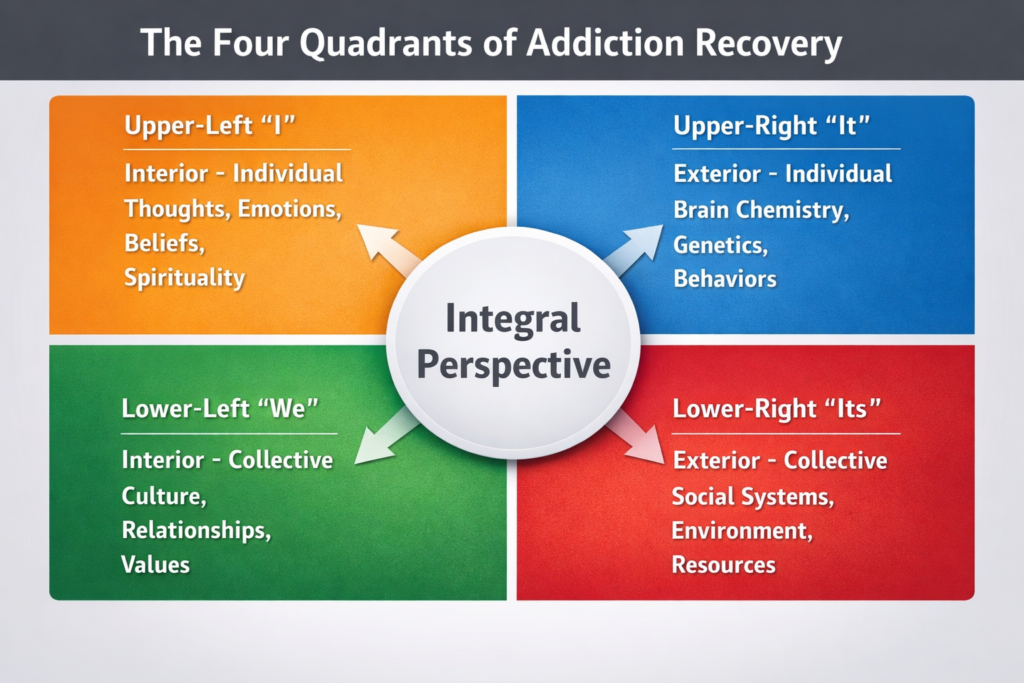

The Four Quadrants: A Diagnostic Map

At the core of Integral theory is a deceptively simple insight: any human phenomenon can be examined from at least four irreducible perspectives. These perspectives—often referred to as the Four Quadrants—do not describe separate realities, but distinct lenses through which the same reality can be understood.

- Upper-Left (Interior–Individual | “I”)

This quadrant concerns subjective experience: thoughts, emotions, beliefs, intentions, identity, meaning, shame, craving, and motivation. It is the domain of psychology, phenomenology, and spirituality—where questions of purpose, agency, and inner conflict arise. - Upper-Right (Exterior–Individual | “It”)

This quadrant addresses observable phenomena: brain chemistry, genetics, physiology, withdrawal processes, habits, and measurable behaviors. It is the domain of neuroscience, medicine, and behavioral analysis. - Lower-Left (Interior–Collective | “We”)

This quadrant encompasses shared meaning systems: culture, values, relational norms, family systems, and recovery communities. It is where belonging, accountability, and stigma exert their influence. - Lower-Right (Exterior–Collective | “Its”)

This quadrant includes social systems and structures: healthcare access, housing stability, economic conditions, institutional policies, and environmental stressors.

Addiction manifests across all four quadrants simultaneously. A person does not simply “have” an addiction. They experience craving and shame (I), driven in part by neurochemical processes (It), within a relational and cultural context that shapes meaning and behavior (We), while navigating social and economic conditions that constrain or enable recovery (Its). An effective recovery architecture must address all four—not necessarily at once, but intentionally over time.

Developmental Readiness and Fit

At earlier stages of development, recovery often begins with damage control systems, where the ego is largely opportunistic and self-driven. At this stage, behavior is governed less by reflection than by impulse, relief-seeking, and short-term advantage. Harm-reduction approaches work precisely because they do not attempt to dismantle the ego outright. Instead, they redirect it. By appealing to self-interest—reducing negative consequences, avoiding legal or relational damage, maintaining access to work or housing—harm-reduction strategies enlist the ego in managing itself more skillfully. When successful, this results in greater stability and self-control, even though the underlying ego structure remains largely intact.

When ego-driven self-management proves insufficient, recovery often requires a more constraining intervention. This is where rules-based meaning systems, such as strict abstinence-oriented programs and inpatient programs at rehabilitation centers, become developmentally appropriate. Here, the ego is no longer trusted to govern itself and must be restrained or subordinated to a higher organizing principle. In Twelve Step programs, this takes the form of surrender to a Higher Power and adherence to communal norms. Psychologically, this represents a shift from opportunistic ego control to externally anchored moral and spiritual authority. For many individuals, this containment is not regressive but necessary, providing a stabilizing structure that the ego alone cannot sustain.

As development continues, individuals may move into a rational-behavioral orientation, where recovery becomes more reflective and evidence-based. At this stage, people begin to analyze patterns, evaluate consequences, and apply cognitive tools to regulate behavior. Building on this, self-authorship represents a further expansion of the self. Rather than relying solely on rational control, self-authorship integrates nonrational dimensions of experience, including emotion, intuition, ritual, creativity, unconscious desire, art, music, and personal symbolism. Recovery becomes less about compliance or control and more about meaning-making, identity formation, and aligning behavior with deeply held values. This transition marks a shift from managing behavior to engaging the whole person.

At the integrative and spiritual-holistic stages, the self-authoring self has usually achieved a significant degree of stability and ease in navigating the world. Perspective is broader, identity is less reactive, and recovery is understood as an ongoing process of integration rather than a fixed endpoint. If addictive behaviors resurface, they are not treated as failure but as signals of misalignment. Intervention at this stage is pragmatic and flexible, often drawing on whatever has worked before, including harm reduction, rules-based containment, rational-behavioral tools, and relational or somatic supports. Discernment replaces ideology, and “whatever works” becomes a mature guiding principle.

In further developments such as Nondual Recovery, the frame shifts again. Rather than viewing addiction primarily as a disease or moral failing, this perspective understands it as a problem of perception, a mistaken sense of separation that drives the search for fulfillment through external means. Healing arises through deeper connection with self, others, and the underlying unity of reality itself. This return to Oneness, or “Not-Two,” reflects a realization of Wholeness in which compulsive patterns lose their organizing power. While vulnerability remains part of being human, alignment with this reality can support expanded consciousness and a more durable freedom from destructive habits.

Conclusion

What distinguishes an Integral Perspective from simple eclecticism is its grounding in a coherent meta-framework. Integrative Recovery, as I use the term, is informed by Ken Wilber’s AQAL model, which holds that a complete account of human experience must attend to quadrants, levels, lines, states, and types. Recovery unfolds across all these dimensions simultaneously. It is biological, psychological, relational, cultural, and systemic; it develops through stages of meaning-making; it expresses itself across multiple lines of addiction; it involves powerful states of consciousness; and it is shaped by enduring differences of personality and identity. Ignoring any of these dimensions prematurely narrows the field of recovery.

Seen this way, recovery is not a single pathway or protocol, but a dynamic and evolving process in which different AQAL elements come into focus at different times. Early recovery may require biological stabilization and external structure, while later phases may emphasize psychological integration, relational repair, or existential and spiritual reorientation. Periods of disruption or relapse may call for a return to earlier supports without shame. The task is not loyalty to a model, but responsiveness to reality as it unfolds.

From this perspective, the central question for both practitioners and people in recovery is not “Which approach is right?” but “Which dimension is most alive right now, and what intervention best meets it?” AQAL offers a disciplined way to ask this question without collapsing into relativism or dogmatism, allowing recovery work to remain flexible without becoming incoherent.

Recovery Made Simple is grounded in this Integral understanding. Its aim is not to promote a single method, but to offer a clear and humane way of thinking about recovery. For clinicians and researchers, it provides a meta-theoretical foundation capable of integrating diverse evidence bases. For people in recovery, it offers permission to draw from multiple traditions without confusion or guilt.

Recovery is not made simple by denying complexity. It is made simpler by seeing clearly.